A curious fact about Canada is that it has no federal abortion law. This feature of abortion is strange on its own, and also strange relative to medical assistance in dying (MAID). The Supreme Court of Canada played an essential role in decriminalizing both abortion and MAID, but after that, each took a different path: abortion has no federal law, while MAID is not only covered in the Criminal Code, but the law has been revised in substantial ways over the past decade.

When I’ve mentioned this before, I’ve framed it as an interesting quirk in trajectories. Carter, the 2015 SCC decision that struck down the general prohibition on assisted dying, might have been the end of the legal story, thereby matching Morgentaler, the 1988 decision that struck down the previous restrictions on abortion. But it turns out this isn’t the whole story, and that, in fact, Canada came about as close as possible to having an abortion law. This story has some important lessons.

A Brief History of Abortion

Prior to 1969, abortion was only legal if a woman’s life was in danger. As a result, there were many illegal abortions. Some physicians accepted cash under the table, but women who couldn’t pay were left to do it themselves or get help from someone who lacked medical training. The outcomes were predictably bad.

In 1969, then-Justice Minister Pierre Trudeau proposed a bill to expand abortion access. It passed, allowing a physician to perform an abortion if a committee deemed that the “life or health” of pregnant woman was endangered. Although this approach increased access, there were still many restrictions. If a woman wanted an abortion, she would have to go before a hospital’s Therapeutic Abortion Committee, made up of at least three physicians in addition to the abortion provider. A committee could only be formed at an ‘accredited’ hospital that met strict criteria, which disqualified many hospitals.

Despite these restrictions, the scope of Trudeau’s bill is impressive. It changed not just abortion, but also decriminalized both acts of homosexuality and being homosexual. Another bill passed at the same time decriminalized contraceptives and introduced laws banning cruelty to animals, among other things. It was these bills that prompted Trudeau’s famous line that “there’s no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation.”

The committee system was in place for nearly two decades until The Supreme Court of Canada decided Morgentaler in January of 1988. Morgentaler didn’t just expand abortion access, it found unconstitutional the entire abortion-related section of the Criminal Code that Trudeau had introduced. Although there was no single majority opinion, a consistent theme is that abortion is, in effect, a value judgment that should be left up to the woman and her physician. Here’s how Chief Justice Brian Dickson put it:

Forcing a woman, by threat of criminal sanction, to carry a foetus to term unless she meets certain criteria unrelated to her own priorities and aspirations, is a profound interference with a woman’s body and thus an infringement of security of the person.

Attempts at a New Law

The Progressive Conservatives led by Brian Mulroney won a landslide victory in 1984, causing the Liberals to lose seventy-three percent of the seats they held under Pierre Trudeau. Morgentaler was decided at the end of Mulroney’s first term. That summer, after Morgentaler but before Mulroney’s government won its second majority, the PCs brought an abortion bill before the House of Commons. Mulroney’s government proposed a compromise bill along the lines of Roe in the United States. It would have permitted abortion early in a pregnancy but prohibited late-term abortions. This motion lost 147 to 76, with many PC MPs voting against it.

The MPs voted on five amendments, including one that would have prohibited abortion in all cases except when the pregnant woman’s health was threatened. This resulted in a narrower loss of 118 to 105.1

An amendment to allow abortions in all cases, so long as they were performed by qualified physicians, was defeated 198 to 20. As it happens, while this was the least popular option in the House of Commons, it’s closest to what the lack of a law ended up producing.

From a government leadership perspective, the situation was a mess. Some MPs wanted more restrictions or a complete ban. Others wanted fewer restrictions or no law at all.

Mulroney led the Progressive Conservatives to a second majority win in the 1988 federal election. It wasn’t the landslide of 1984, but it was still a decisive victory. Although abortion wasn’t the key issue of the 1988 election, Morgentaler was a factor. During his campaign, Mulroney avoided taking a firm stand on abortion, but said that, if elected, his government would pass an abortion law.

Some of the reasons people wanted an abortion law are predictable. Neither the PCs nor the Liberals as parties had a unified vision of what the law should be, but some members of parliament were pro-life and believed that even the restricted abortion landscape pre-Morgentaler was too permissive. Since Morgentaler meant there were no restrictions—creating so-called ‘abortion on demand’—they believed that it would lead to an increase in the number of abortions.

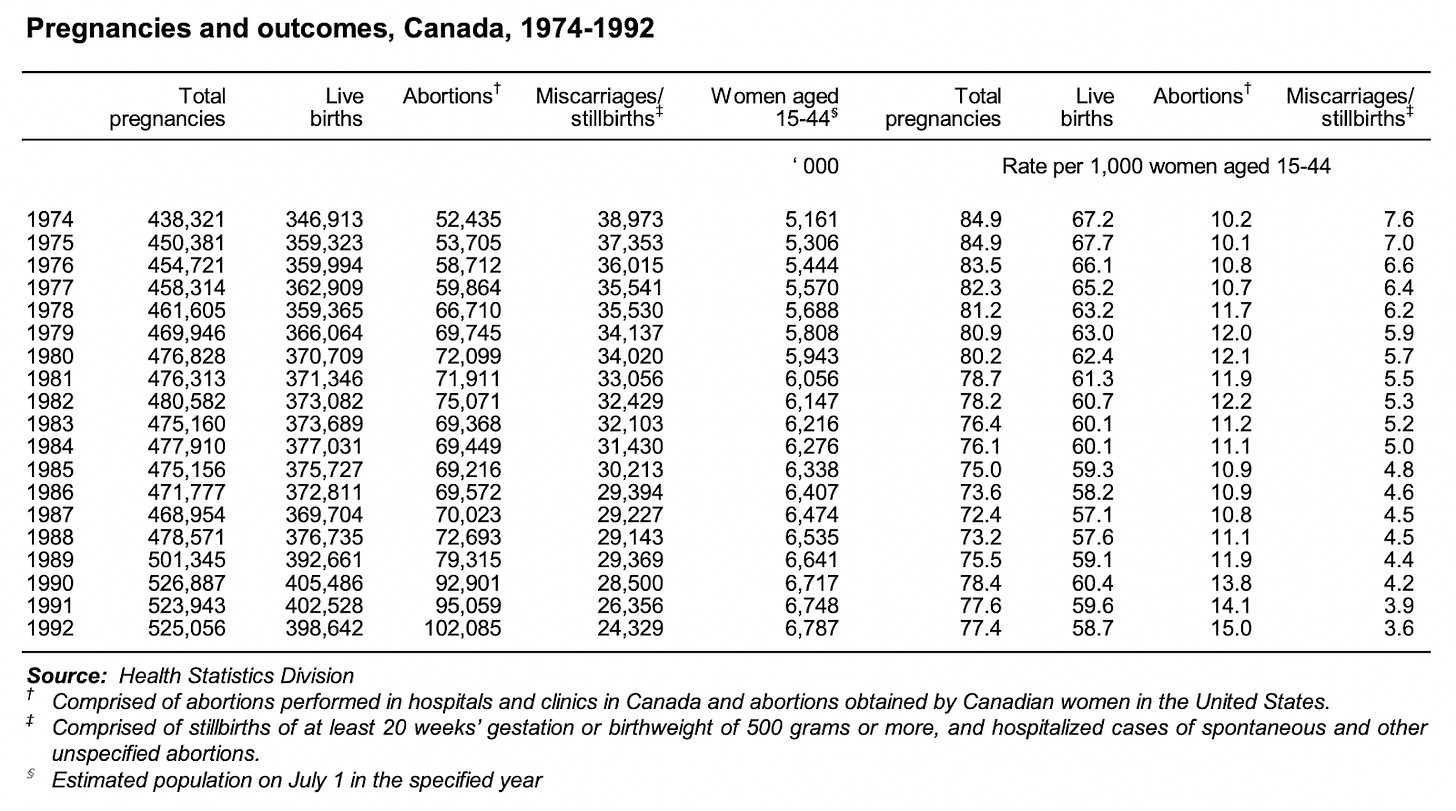

On this point, they were correct. To jump forward a bit, a Statistics Canada analysis from 1996 shows how abortion rates rose from the mid-1970s into the mid-1990s. But the authors note that both the raw numbers and the rate per 1,000 women masks how significant the change really was.

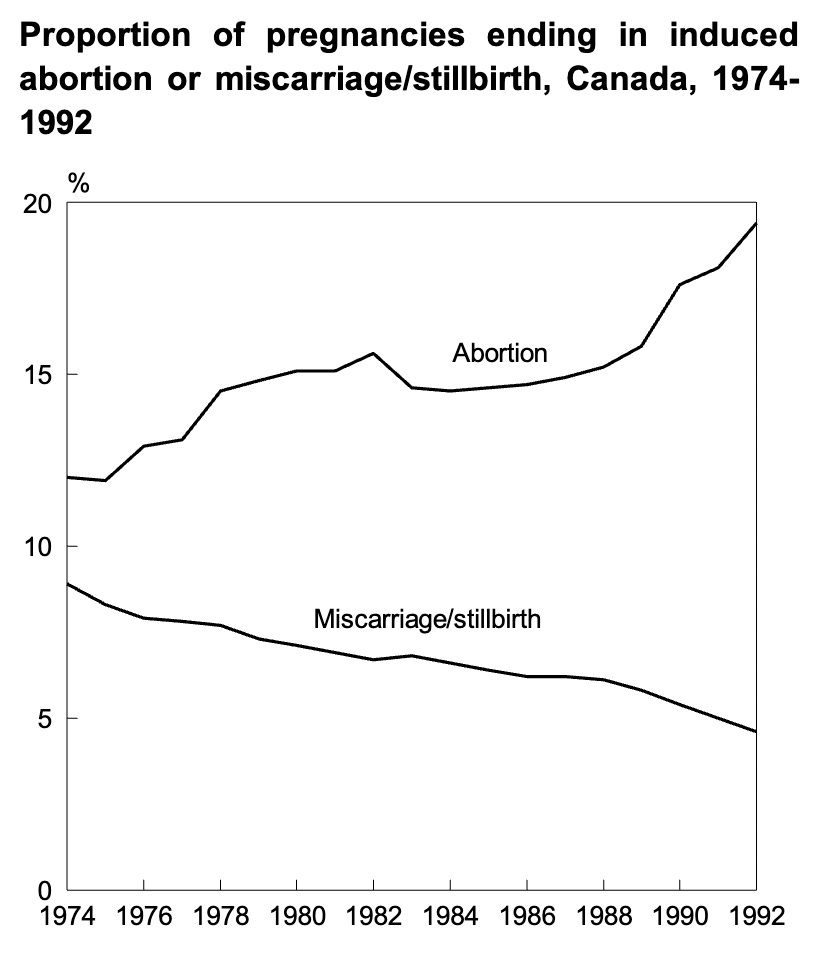

A second chart shows the situation more clearly: the number of pregnancies ended by abortion rose from twelve percent in 1976 to over nineteen percent in 1992, with a noticeable jump following 1988, the year Morgentaler was decided. Hoping to stop this trend, pro-life groups lobbied Mulroney’s party for a restrictive law.

There were other, less obvious reasons for a law. One was a worry that, without one, so-called ‘back-alley’ abortions would proliferate, since, the thought went, people wouldn’t be deterred by the threat of prosecution. This prediction turned out to be false, and there’s no evidence of a rise in abortions performed by people who weren’t healthcare providers.

Mulroney’s first attempt at a law fizzled out, but he tried again in his second term. This bill, C-43, developed momentum in parliament. It proposed amending the Criminal Code to read as follows:

287. (1) Every person who induces an abortion on a female person is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years, unless the abortion is induced by or under the direction of a medical practitioner who is of the opinion that, if the abortion were not induced, the health or life of the female person would be likely to be threatened.

(2) For the purposes of this section, “health” includes, for greater certainty, physical, mental and psychological health; “medical practitioner,” in respect of an abortion induced in a province, means a person who is entitled to practise medicine under the laws of that province.

Essentially, the bill, if passed, would return the law to what it was pre-Morgentaler, minus the committees. Conservative lawmakers were betting that the Supreme Court would strike down another committee structure but would allow the health-related criteria introduced by Trudeau. These criteria were purposely broad and ambiguous.

Mulroney’s case for taking this approach was simply that it had the best chance of passing in the House of Commons. And in May 1990, it narrowly did—140 to 131—sending it to the Senate for debate and, possibly, approval.

The period before the Senate’s vote was intense. Different sources give different numbers, but many physicians stopped performing abortions, in some cases because of worries about future prosecution, and sometimes because anti-abortion protesting was so intense.2 One article describes how anti-abortionists broke into a Vancouver abortion clinic and destroyed medical equipment. An anti-abortion group then bought the house next to the clinic so as to protest more regularly.3

Such protests were common at clinics across Canada, and they only got more intense in the following years. In 1994, a terrorist shot Garson Romalis, an abortion provider in Vancouver, while he was eating breakfast in his home. It took him two years to return to work. Then, in 2000, he was stabbed, which also led to serious injuries. Other providers have been shot, threatened, or interfered with (protesters regularly put nails on Romalis’s driveway).

The Senate was also still affected by the passage of the General Sales Tax. In 1989, Mulroney proposed a federal sales tax. This move was extremely unpopular among Canadians, but Mulroney’s majority government was able to get it through the House of Commons. At the time, the majority of senators were Liberals who refused to pass the bill. To get around this, Mulroney temporarily appointed eight senators. The bill passed and became law (though the tax rate was lowered to seven percent from the initially proposed nine percent).

The Senate wasn’t happy about this move, which, while legal, was widely criticized. And there were fears that Mulroney might attempt it again with C-43. In the end, he didn’t, but what happened instead is even stranger. When it came to a vote on January 30th, 1991, there was a tie. In the House of Commons, the Speaker votes to break a tie, but in the Senate, the Speaker isn’t a tiebreaker. Instead, the vote failed to pass.

In news articles in the days following the vote, every side seemed to declare victory. The Kitchener-Waterloo Record ran a story with the headline “No New Abortion Law Planned: Both Sides of Controversy Welcome Death of Bill C-43”. Pro-choice advocates were pleased that the restrictions weren’t reimplemented, but many pro-lifers also claimed victory:

Anneliese Steden, spokesperson for the Cambridge Right to Life, said the organization was “hoping” Bill C-43 would be defeated because it was “paraded as a pro-life bill when it wasn’t.”

The Campaign Life Coalition and Alliance for Life, along with local Right to Life groups took a “strong stand against the bill,” believing that no law was better than a bad one, she said.

“In our opinion we would be better off without a law and try to get a better law in the future,” Steden said. “We felt what the government called a compromise bill, wasn’t. It didn’t pacify anyone.”

Lack of support from pro-life groups turned out to be a key reason the bill didn’t pass. The Edmonton Journal ran an interview a few months before the Senate vote with a pro-life advocate who was against C-43 :

“It’s an open-ended option. Now only one doctor has to approve the abortion, (under old legislation) a panel of three did,” said Susan McNeely, vice-president of Campaign Life. She believes the terms “medical, mental and psychological” are too vague and all-encompassing.4

Some of the senators who voted against the bill for pro-life reasons, such as Toronto senator Stanley Haidasz, were Liberal.5 But, for me, the most interesting story is of Pat Carney, a Conservative senator. An article in the Globe following her death in 2023 describes what happened behind the scenes:

The day before the vote, Ms. Carney recounted later, “in a threatening voice that chilled me to the bone,” [Justice Minister Kim] Campbell warned her against voting “no.” In her journal, she wrote “Heavy, heavy pressure.” The next day, undeterred, Ms. Carney was the first Conservative senator to stand and vote against the bill. Six Conservative senators followed, several of whom told her they had intended to abstain but changed their minds when they saw her vote.

Because of this, Conservative leadership removed Carney from a key committee a few days later.

Lessons

For me, there are a few key takeaways from this. In What We Owe the Future, the philosopher William MacAskill describes how change is much easier in some periods than others. He calls this plasticity. This was certainly true of Morgentaler itself and the few years after, and it wasn’t lost on Justice Minister Kim Campbell, who, following the Senate vote, “admitted the longer the country goes without an abortion law, the more difficult it will become for any future government to introduce one”. It has been over thirty years and Canada still doesn’t have an abortion law. There was a brief period when the window to a new abortion law was open, but it closed and might never open again.

It’s also worth noting how badly the pro-choice groups overplayed their hand. According to Steden, the spokesperson for Cambridge Right to Life whom I quoted earlier, the plan following the failed Senate vote was to push to have more pro-life politicians elected in order to pass a stronger bill, which never happened in any serious way. She said that “no law was better than a bad one”, which is doubtful in hindsight.

My view is that what we have with abortion is what we should have with many aspects of healthcare, including MAID, so I’m glad the Senate vote failed. But the bigger political point is that, without the benefit of hindsight, sometimes it’s better to settle for a result in the right direction instead of being an absolutist. This is a lesson for MAID, climate change, and many other areas.

Bindman, S., The Ottawa Citizen (1988, Jul 29). Abortion motions rejected; govt. given little help on new law: [final edition].

Cox, B., Kitchener-Waterloo Record (1991, Jan 15). Experts fear doctors will refuse abortions if bill C-43 is passed: [city edition].

Cox, B., Kitchener-Waterloo Record (1991, Jan 15). Experts fear doctors will refuse abortions if bill C-43 is passed: [city edition].

Sherlock, K. Edmonton Journal (1990, Oct 13). Law called major threat to abortion; president of college says bill C-43 affects 95 per cent of those done now: [FINAL edition].

Walker, W. Toronto Star (1991, Jan 30). Senator criticizes abortion bill 'flaws': [FIN edition].

Thank you for this. I marched for Dr Morganthaler in the 60s and would do it again. Your historical analysis is important

Nice historical analysis. I doubt that it is possible to have any law dealing with abortion that is not fatally vague if it is part of the Criminal Code because physicians will never know what is meant by the key words like health being "threatened". They will never know if they are being merciful or criminal. The vague equivalent in MAID law is death being "reasonably foreseeable".