If you want to decriminalize drugs, you can't get rid of the police

The best policy balances two goals

Yesterday was the two-year anniversary of British Columbia’s experiment with decriminalizing drug possession. Last year, B.C. added restrictions that weren’t in the original exemption, but the core law remains in place. Meanwhile, Oregon, which had decriminalized possession in 2020, reversed course last year by reintroducing more severe criminal penalties. There are some important lessons here.

First, some background. In Oregon’s case, a 2020 referendum passed Measure 110, the Drug Addiction Treatment and Recovery Act, with fifty-eight percent of voters in favour. Beginning in February 2021, the act directed money from the legal sale of cannabis to drug treatment programs and, more significantly, reduced the penalty for possessing small amounts of many drugs—including heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, and fentanyl—to a fine of one hundred dollars. The fine would be waived if the person completed a health assessment at an addiction recovery center, and failure to pay the fine wouldn’t lead to more fines or imprisonment.

British Columbia’s legal pathway to decriminalization was different, but the practical details were similar. In contrast to Oregon, which passed a law decriminalizing drugs, British Columbia received a three-year exemption from Health Canada, after which there will be an assessment and, perhaps, a renewal of the program. Since January 31st, 2023, possessing small amounts of certain drugs—heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, and fentanyl—no longer leads to arrest. Instead, police officers are instructed to offer health information. Last May, the law changed to recriminalize possession in public spaces, though possession is permitted in private residences and “places unhoused individuals are legally sheltering (indoor and outdoor locations).”

Many people predicted that decriminalizing drugs, including fentanyl, would cause a sharp rise in overdoses. I shared this worry, for reasons I describe below. But let’s first look at the data. For context, here’s drug overdose deaths for the United States:

Here’s Oregon. Decriminalization took effect February 1st, 2021.

Compared to the entire U.S., Oregon experienced a much larger spike in overdoses, and although the rate of increase didn’t change significantly post-decriminalization, it rose much more steeply than the U.S. overall. In fact, from September 2022 to September 2023, Oregon saw the largest increase in drug-related deaths in the country.

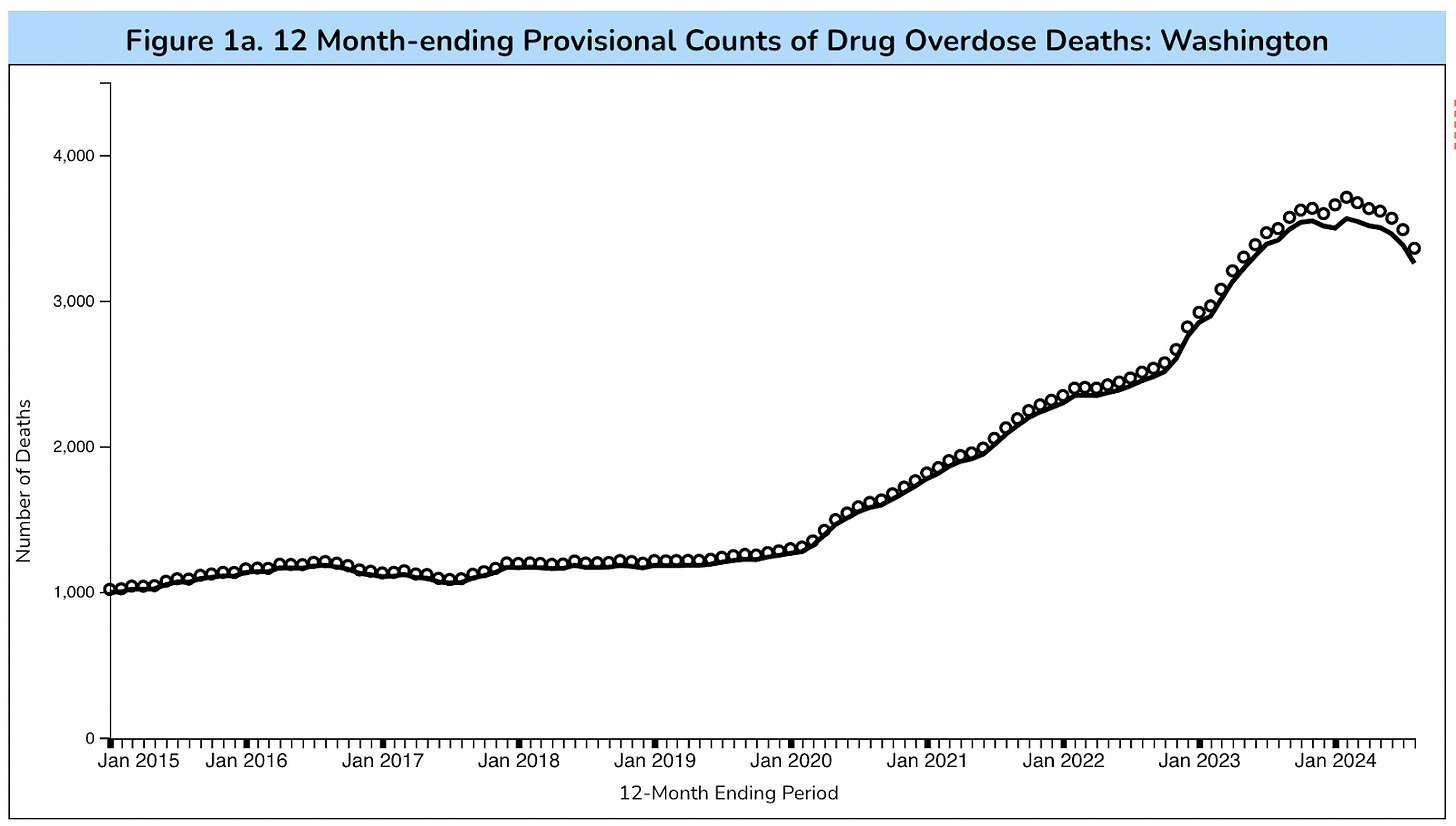

However, decriminalization doesn’t seem to have been the driver. For context, here’s Washington, which didn’t change its laws:

The rate of overdose deaths was similar, which raises doubts that decriminalization was driving overdose rates. Research bears out this finding: A study in JAMA Psychiatry found no association between the change in Oregon’s law and overdose deaths one year after decriminalization. Another study, which was published last year in JAMA Network Open, similarly found no association over a longer period. This means that, whatever the factors that led to a rise in overdose deaths in the Pacific Northwest, decriminalization doesn’t seem to have been the cause.

Now to British Columbia. Here’s opioid deaths for all of Canada:

Here’s British Columbia. The hash lines begin when B.C. began grouping all deaths due to unregulated drugs instead of just opioids.

As with Oregon, there’s no clear association between decriminalization and overdoses. The first three quarters following the exemption saw overdoses go down or remain flat, while Canada saw a slight increase.

Oregon’s decriminalization experiment lasted for three years before it was repealed, and British Columbia’s is, as of yesterday, two years old. This is enough time to identify trends, but longer-term changes, both good or bad, are still possible.

In terms of overdose deaths, things turned out better than I thought they would. Over eighty percent of drug overdoses involve non-pharmaceutical drugs—i.e., drugs made illegally—usually because people take drugs without knowing their strength or quantity. In the last decade, those drugs have increasingly contained fentanyl, which has caused the majority of overdoses.

My concern was that, although trafficking and selling drugs remained illegal in both places, decriminalization would lead to more sales, which would cause more overdoses. The good news is that the rise of overdoses because of decriminalization didn’t happen. Still, I continue to think that an important way of addressing overdoses is to change the supply so that people know what they’re using. If not, as Brittany Graham, executive director of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users, told the Washington Post, “It’s you going to the liquor store thinking you’re going to get alcohol and you’re getting poison, you’re getting turpentine.”

There’s a broader trend playing out in all the charts above. As they show, the number of overdose deaths in both the United States and Canada has been declining. In Canada, opioid toxicity deaths are down eleven percent from the same point last year, while hospitalizations are down ten percent. In the U.S., the drop is even steeper. This is likely due to multiple factors, including that naloxone is increasingly available and that fentanyl is getting harder to find and more adulterated (i.e., less strong). Disrupting the drug cartels appears to be paying off.

The Effects of Public Drug Use

From the beginning, both jurisdictions stated that reducing drug-related arrests was a key feature of their strategies. As Measure 110 puts it, “ The people of Oregon further find that a health-based approach to addiction and overdose is more effective, humane and cost-effective than criminal punishments.” Likewise, B.C.’s webpage on decriminalization begins by stating that “Addiction is a health issue, not a criminal one.”

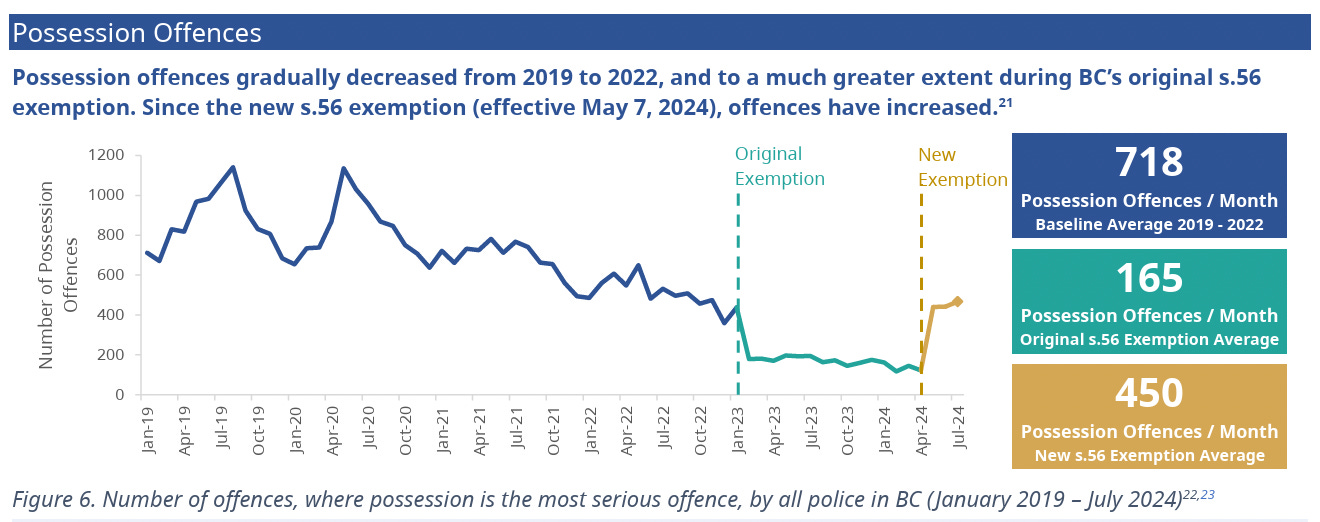

Predictably, removing legal penalties for drug possession led to dramatic decreases in these arrests in both jurisdictions (though B.C.’s has returned to pre-exemption levels following the added restrictions from last year). Here’s B.C.:

The problem is that both places experienced a predictable effect of removing penalties for public drug possession: A lot of people started using drugs in public. It’s hard to quantify the change, since the main way of measuring public drug use was police involvement. Once the police stopped making arrests, the effects became less measurable. But still, people noticed a clear uptick in public drug use.

I saw this for myself when I visited Portland in 2022, which was the first time I had been there in over a decade. Downtown Portland, which I remembered as a nice place, had become rough. Open drug use, break-ins, and thefts had already led some downtown stores to close, but the closing of Portland’s only REI in 2023 was a breaking point for many. In the months that followed, politicians increasingly began calling for recriminalization.

Oregon is correct that criminal punishments aren’t going to solve addiction, but they put themselves in a bind by making it impossible for the police to get involved. This was part of the larger anti-police trend that started in 2020. Decriminalization came in the wake of Portland cutting $15 million from the police budget in 2020, which was significant, though not the $50 million cut “Defund the Police” activists called for.

If the fine for drug possession is only a hundred dollars, and you know that you can’t be additionally fined or arrested, then you’ll be much more inclined to do drugs out in the open, which is what happened.

The same trend has played out in Portugal, which decriminalized drugs in 2001 and was a model for Oregon. In the years following decriminalization, Portugal had some big wins: HIV, drug overdoses, and incarceration rates all fell. But there has been a large increase in public drug use in the post-Covid years, which has led politicians to begin calling for a different approach.

All of this means that we should pursue two goals simultaneously: allowing people to use drugs while not allowing them to use drugs disruptively in public. People should be free to use drugs if they want to, and, since they’re going to do so whether or not those drugs are legal, a war-on-drugs approach is neither going to stop drug use nor help people who want treatment for addiction (though, importantly, people use drugs, including drugs such as heroin, without being addicted to them). At the same time, the right to use drugs doesn’t outweigh the value of well-functioning urban spaces of the sort downtown Portland used to have.

The upshot of this is that we need police who can maintain the latter without interfering with the former. Progressives have made some serious mistakes in the last decade, but it’s hard to think of a bigger one—both politically and practically—than the ‘Defund the Police’ movement. The evidence is clear that policing reduces violent crime. Politically, support for defunding the police among Blacks and Hispanics was low to begin with and only fell as the movement got attention, but many progressives are still surprised by rising Black and Hispanic support for Trump while missing this sort of data.

Rui Moreira, the mayor of Porto, Portugal, describes how the goals have become unbalanced in his city. “These days in Portugal, it is forbidden to smoke tobacco outside a school or a hospital. It is forbidden to advertise ice cream and sugar candies. And yet, it is allowed for [people] to be there, injecting drugs,” he told the Washington Post.

Allowing people to use drugs while not allowing them to use them disruptively in public leads to tradeoffs, but this isn’t a new problem. Canada and the U.S. allow people to drink alcohol, smoke tobacco, and, in some places, use cannabis, but we restrict the public consumption of these substances. Toronto now allows alcohol consumption in many public parks, but the City is clear that “Public intoxication and disruptive behaviour including public urination are not allowed.”

Adding other drugs requires different strategies, such as safe-consumption sites, but not a different set of values. It’s also important that, as is the case with problems purportedly related to MAID, these issues are partly downstream of broader trends, such as a lack of affordable housing. This is an issue Portland and Vancouver have done a particularly bad job of addressing.

I support not just decriminalizing drug possession, but providing pharmaceutical-grade drugs, since the cause of most overdoses is street drugs, not drug use per se. But it’s a mistake to conclude that there’s no need for policing. Even if you disagree, Oregon is evidence that even one of the most decriminalization-friendly places in the world isn’t going to allow drug use at all costs, so the only viable strategy is to balance the goals.

Thanks for this article. Scary reporting but enlightening.

I was just reading an article from the NZZ(new Zurich News, Switzerland) which also extensively covered the subject of the decriminalization of hard drugs in my beloved home state. Lordy. Scary stuff what’s continuing to go down.

Here:

Oregon pays the price for being the first US state to decriminalize hard drugshttps://www.nzz.ch/english/oregon-reverses-course-after-drug-policy-fiasco-ld.1831918